Before the birth of Adolf Hitler the family surname had many variations that were often used almost interchangeably. Some of the common variances were Hitler, Hiedler, Hüttler, Hytler, and Hittler. Alois Schicklgruber (Adolf's father) changed his name on 7 January 1877 to "Hitler", which was the only form of the last name that Adolf used.[2]

The family has long been of interest to historians and genealogists because of the uncertain biological paternity of Hitler's father as well as the family's inter-relationships and their psychological effect on Hitler during his childhood.

Etymology[edit]

Hitler is a spelling variation of the name Hiedler, meaning one who resides by a Hiedl - in Austro-Bavarian dialects a term for a subterranean fountain or river.[3]

Family history[edit]

Earliest family members[edit]

"The Hitler family descends from Stefan Hiedler (born 1672) and his wife, Agnes Capeller. Their grandson was Martin Hiedler (17 November 1762 – 10 January 1829), who married Anna Maria Göschl (23 August 1760 – 7 December 1854). Martin and Anna were the parents of at least three children, Lorenz, about whom there is no further information, Johann Georg (baptised 28 February 1792 – 9 February 1857), who was the stepfather of Alois Hitler (father of Adolf), and Johann Nepomuk (19 March 1807 – 17 September 1888), a maternal great-grandfather of Adolf Hitler.[2] They were from Spital (part of Weitra), Austria."

Johann Georg and Johann Nepomuk[edit]

Johann Georg was legitimized and considered the officially accepted paternal grandfather of Hitler by the Third Reich. Whether he was actually Hitler's biological paternal grandfather remains unknown. He married his first wife in 1824, but she died in childbirth five months later. In 1842, he married Maria Anna Schicklgruber (15 April 1795 – 7 January 1847) and became the legal stepfather to her illegitimate five-year-old son, Alois.

Around age 10, near the time of his mother's death, Alois went to live with Joahann Nepomuk on his farm. Johann Nepomuk Hiedler (also known as Johann Nepomuk Hüttler) was named after a Bohemian saint, Johann von Nepomuk. Some view this name as evidence that Johann Nepomuk and therefore his great-grandson Adolf Hitler had some Czech blood.[citation needed] However, Johann von Pomuk/Johann Nepomuk was an important saint for Bohemians of both Germanand Czech ethnicity. The name "Nepomuk" merely indicates ties to Bohemia, without indication of ethnicity. Johann Nepomuk became a relatively prosperous farmer and was married to Eva Maria Decker (1792–1873), who was fifteen years his senior.

The Nazis issued a pamphlet during the 1932 second elections campaign titled "Facts and Lies about Hitler" which refuted the rumour spread by the S.P.D. and Center Party that he had Czech ancestors.[6] There is no evidence that any of Hitler's known ancestors were of Czech origin.[7]

Father of Alois Hitler[edit]

The identity of Alois' biological father is disputed. Legally, Johann Nepomuk was the step-uncle of Alois Schicklgruber (later Alois Hitler), and Johann Nepomuk's brother Johann Georg Hiedler, a wandering miller, was Alois's step-father.[8] For reasons unknown, Johann Nepomuk took in Alois when he was a boy and raised him. It is possible that he was, in fact, Alois's natural father but could not acknowledge this publicly due to his marriage. Another, perhaps simpler, explanation is that he took pity on the ten-year-old Alois after the death of Alois' mother Maria, as it could hardly have been a suitable life for a ten-year-old child to be raised by an itinerant miller.

Johann Nepomuk died on 17 September 1888 and left Alois a considerable portion of his life savings. Johann Nepomuk's granddaughter, Klara, had a longstanding affair with Alois before marrying him in 1885 after the death of his second wife. In 1889, she gave birth to Adolf Hitler.

It was later claimed that Johann Georg had fathered Alois prior to his marriage to Maria, although Alois had been declared illegitimate on his birth certificate and baptism papers. The claim that Johann Georg was the true father of Alois was not made after the marriage of Maria and Johann Georg, or, indeed, even during the lifetime of either of them. In 1877, 20 years after the death of Johann Georg and almost 30 years after the death of Maria, Alois was legally declared to have been Johann Georg's son.[9]

Accordingly, Johann Georg Hiedler is one of three people often cited as having possibly been the biological grandfather of Adolf Hitler. The other two are Johann Nepomuk and a Graz Jew by the name of Leopold Frankenberger (rumored by ex-Nazi Hans Frank during the Nuremberg Trials). In the 1950s, the third possibility became popular among historians, but modern historians have concluded that Frank's speculation has no factual support. Frank said that Maria came from "Leonding near Linz", when in fact she came from the hamlet of Strones, near the village of Döllersheim. No evidence has ever been found that a "Frankenberger" lived in the area; the Jews were expelled from Styria (which includes Graz) in the 15th century and were not permitted to return until the 1860s, several decades after Alois' birth.[10][11][12] Although Alois was legitimized and Johann Georg was considered the officially accepted paternal grandfather of Hitler by the Third Reich, whether he was Hitler's biological grandfather remains unknown and has caused speculation.[13][14][15] However, his case is considered the most plausible and widely accepted.

Pölzl family[edit]

Johanna Hiedler, the daughter of Johann Nepomuk and Eva Hiedler (née Decker) was born on 19 January 1830 in Spital (part of Weitra) in the Waldviertel of Lower Austria. She lived her entire life there and was married to Johann Baptist Pölzl (1825–1901), a farmer and son of Johann Pölzl and Juliana (Walli) Pölzl. Johanna and Johann had 5 sons and 6 daughters, of whom 2 sons and 3 daughters survived into adulthood, the 3 daughters being Klara, Johanna, and Theresia.

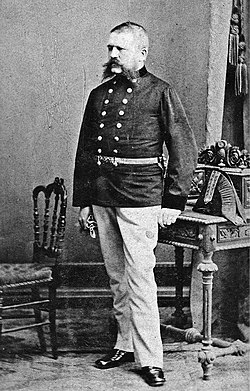

Main article: Alois Hitler

At the age of 36, Alois Hitler was married for the first time, to Anna Glasl-Hörer, who was a wealthy, 50-year-old daughter of a customs official. She was sick when Alois married her and was either an invalid or became one shortly afterwards. Not long after marrying her, Alois Hitler began an affair with 19-year-old Franziska "Fanni" Matzelsberger, one of the young female servants employed at the Pommer Inn, house #219, in the city of Braunau am Inn, where he was renting the top floor as a lodging. Smith states that Alois had numerous affairs in the 1870s, resulting in his wife initiating legal action; on 7 November 1880 Alois and Anna separated by mutual agreement. Matzelsberger became the 43-year-old Hitler's girlfriend, but the two could not marry since under Roman Catholic canon law, divorce is not permitted. In 1876, three years after Alois married Anna, he hired Klara Pölzl as a household servant. She was the 16-year-old granddaughter of his step-uncle (and possible father or biological uncle) Nepomuk. If Nepomuk was Alois' father, Klara was Alois' half-niece. If his father was Johann Georg, she was his first cousin once removed. Matzelsberger demanded that the "servant girl" Klara find another job, and Hitler sent Pölzl away.

On 13 January 1882, Matzelsberger gave birth to Hitler's illegitimate son, also named Alois, but since they were not married, the child was Alois Matzelsberger. Hitler kept Matzelsberger as his wife while his lawful wife Anna grew sicker and died on 6 April 1883. The next month, on 22 May at a ceremony in Braunau with fellow customs officials as witnesses, Hitler, 45, married Matzelsberger, 21. He then legitimized his son as Alois Hitler, Jr.[16] Matzelsberger went to Vienna to give birth to Angela Hitler. When she was still only 23, she acquired a lung disorder and became too ill to function. She was moved to Ranshofen, a small village near Braunau. During the last months of Matzelsberger's life, Klara Pölzl returned to Alois' home to look after the invalid and their two children.[17] Matzelsberger died in Ranshofen on 10 August 1884 at the age of 23. After her death, Pölzl remained in Hitler's home as housekeeper.[17]

Pölzl was soon pregnant by Alois. Smith writes that if Hitler had been free to do as he wished, he would have married Pölzl immediately, but because of the affidavit concerning his paternity, Hitler was now legally Pölzl's first cousin once removed, too close to marry. He submitted an appeal to the church for a humanitarian waiver.[18]Permission came, and on 7 January 1885 a wedding was held at Hitler's rented rooms on the top floor of the Pommer Inn. A meal was served for the few guests and witnesses. Hitler then went to work for the rest of the day. Even Klara found the wedding to be a short ceremony. Throughout the marriage, she continued to call him uncle.

On 17 May 1885, five months after the wedding, the new Frau Klara Hitler gave birth to her first child, Gustav. A year later, on 25 September 1886, she gave birth to a daughter, Ida. Her son Otto followed Ida in 1887, but he died shortly after birth.[19] During the winter of 1887–1888, diphtheria struck the Hitler household, resulting in the deaths of both Gustav (8 December) and Ida (2 January). Klara and Alois had been married for three years, and all their children were dead, but Alois still had the children from his relationship with Matzelsberger, Alois Jr., and Angela. On 20 April 1889, Klara gave birth to Adolf.

Infant Adolf, son of Alois and Klara.

Adolf was a sickly child, and his mother fretted over him. Alois, who was 51 when Adolf was born, had little interest in child rearing and left it all to his wife. When not at work he was either in a tavern or busy with his hobby: keeping bees. In 1892, Alois was transferred from Braunau to Passau. He was 55, Klara 32, Alois Jr. 10, Angela 9, and Adolf 3 years old. In 1894, Alois Hitler was reassigned to Linz. Klara gave birth to their fifth child, Edmund, on 24 March 1894, and it was decided that she and the children would stay in Passau for the time being.

In February 1895, Alois Hitler purchased a house on a 9-acre (36,000 m²) plot in Hafeld near Lambach, approximately 30 miles (48 km) southwest of Linz. The farm was called the Rauscher Gut. He moved his family to the farm and retired on 25 June 1895 at the age of 58 after 40 years in the customs service. He found farming difficult; he lost money, and the value of the property declined. On 21 January 1896, Paula was born. Alois was often home with his family. He had five children ranging in age from infancy to 14; Smith suggests he yelled at the children almost continually and made long visits to the local tavern. Robert G. L. Waite noted, "Even one of his closest friends admitted that Alois was 'awfully rough' with his wife [Klara] and 'hardly ever spoke a word to her at home.'" If Hitler was in a bad mood, he picked on the older children or Klara herself, in front of the rest.

After Hitler and his oldest son Alois Jr had a violent argument, Alois Jr left home at 14, and the elder Alois swore he would never give the boy a penny of inheritance beyond what the law required. Apparently Alois Jr's relations with his stepmother Klara were also strained. After working as an apprentice waiter in the Shelbourne Hotel in Dublin, Ireland, Alois Jr was arrested for theft and served a five-month sentence in 1900, followed by an eight-month sentence in 1902.

Edmund, the youngest Hitler boy, died of measles on 2 February 1900. Alois wanted his son Adolf to seek a career in the civil service. However, Adolf had become so alienated from his father that he was repulsed by whatever Alois wanted. Adolf sneered at the thought of a lifetime spent enforcing petty rules. Alois tried to browbeat his son into obedience while Adolf did his best to be the opposite of whatever his father wanted.

Alois Hitler died in 1903, leaving Klara a government pension. She sold the house in Leonding and moved with young Adolf and Paula to an apartment in Linz, where they lived frugally. Three or four years later a tumor was diagnosed in her breast. Following a long series of painful iodoform treatments given by her doctor Eduard Bloch, Klara died at home in Linz on 21 December 1907. Adolf and Paula were at her side.[20][21] The siblings were left with some financial support from their mother's pension and her modest estate. Klara was buried in Leonding.

Hitler had a close relationship with his mother, was crushed by her death and carried the grief for the rest of his life. Speaking of Hitler, Bloch later recalled that after Klara's death he had seen in "one young man never so much pain and suffering".[22]

On 14 September 1903[23][24] Angela Hitler, Adolf's half-sister, married Leo Raubal (11 June 1879 – 10 August 1910), a junior tax inspector, and on 12 October 1906 she gave birth to a son, Leo. On 4 June 1908 Angela gave birth to Geli and in 1910 to a second daughter, Elfriede (Elfriede Maria Hochegger, 10 January 1910 – 24 September 1993).

In 1909, Alois Hitler, Jr. met an Irishwoman by the name of Bridget Dowling at the Dublin Horse Show. They eloped toLondon and married on 3 June 1910. William Dowling, Bridget's father, threatened to have Alois arrested for kidnapping, but Bridget dissuaded him. The couple settled in Liverpool, where their son William Patrick Hitler was born in 1911. The family lived in a flat at 102 Upper Stanhope Street. The house was destroyed in the last German air-raid on Liverpool on 10 January 1942. Nothing remains of the house or those that surrounded it, and the area was eventually cleared and grassed over. Bridget Dowling's memoirs claim Hitler lived with them in Liverpool from 1912 to 1913 while he was on the run to avoid being conscripted in his native Austria-Hungary, but most historians dismiss this story as a fiction invented to make the book more appealing to publishers.[25] Alois attempted to make money by running a small restaurant in Dale Street, a boarding house on Parliament Street and a hotel on Mount Pleasant, all of which failed. Alois Jr. left his family in May 1914 and he returned alone to the German Empire to establish himself in the safety-razor business.

Paula had moved to Vienna, where she worked as a secretary. She did not have contact with Hitler during the period comprising his difficult years as a painter in Vienna and later Munich, military service during the First World War and early political activities back in Munich. She was delighted to meet him again in Vienna during the early 1920s, though she later claimed to have been privately distraught at his subsequent rising fame.

First World War[edit]

When the First World War broke out, Alois Jr. was stranded in Germany and it was impossible for his wife and son to join him. He married another woman, Hedwig Heidemann (or Hedwig Mickley[26]), in 1916. After the war, a third party informed Bridget that he was dead.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Hitler was a resident of Munich and volunteered to serve in the Bavarian Army as an Austrian citizen. Posted to the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 (1st Company of the List Regiment). Hitler's case was not exceptional as he was not the only Austrian soldier in the List Regiment. It is likely Hitler was accepted into the Bavarian army either simply because nobody had asked him whether he was a German citizen when he first volunteered or because the recruiting authorities were happy to accept any volunteer and simply did not care what Hitler's nationality was, or because he might have told the Bavarian authorities that he intended to become a German citizen.

Hitler (middle right) with his army comrades of the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 (c. 1914–1918)

He was decorated for bravery, receiving the Iron Cross, Second Class, in 1914.Recommended by Hugo Gutmann, he received the Iron Cross, First Class, on 4 August 1918, a decoration rarely awarded to one of Hitler's rank (Gefreiter). Hitler's post at regimental headquarters, providing frequent interactions with senior officers, may have helped him receive this decoration. Though his rewarded actions may have been courageous, they were probably not highly exceptional.He also received the Black Wound Badge on 18 May 1918.

During his service at the headquarters, Hitler pursued his artwork, drawing cartoons, and instructions for an army newspaper. During the Battle of the Somme in October 1916, he was wounded either in the groin area or the left thigh by a shell that had exploded in the dispatch runners' dugout.

Hitler as a soldier during the First World War (1914–1918)

Hitler spent almost two months in the Red Cross hospital at Beelitz, returning to his regiment on 5 March 1917. On 15 October 1918, he was temporarily blinded by a mustard gasattack and was hospitalised in Pasewalk. While there, Hitler learnt of Germany's defeat,and—by his own account—on receiving this news, he suffered a second bout of blindness.

Hitler became embittered over the collapse of the war effort, and his ideological development began to firmly take shape. He described the war as "the greatest of all experiences", and was praised by his commanding officers for his bravery. The experience reinforced his passionate German patriotism and he was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918. Like other German nationalists, he believed in the Dolchstoßlegende (stab-in-the-back legend), which claimed that the German army, "undefeated in the field", had been "stabbed in the back" on the home front by civilian leaders and Marxists, later dubbed the "November criminals".

The Treaty of Versailles stipulated that Germany must relinquish several of its territories anddemilitarise the Rhineland. The treaty imposed economic sanctions and levied heavy reparations on the country. Many Germans perceived the treaty—especially Article 231, which declared Germany responsible for the war—as a humiliation. The Versailles Treaty and the economic, social, and political conditions in Germany after the war were later exploited by Hitler for political gains.

On 14 March 1920, Heinrich "Heinz" Hitler was born to Alois Jr and his second wife, Hedwig Heidemann. In 1924, Alois Jr was prosecuted for bigamy, but acquitted due to Bridget's intervention on his behalf. His older son, William Patrick, stayed with Alois and his new family during his early trips to Weimar Republic Germany in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

When Adolf was confined in Landsberg, Angela made the trip from Vienna to visit him. Angela's daughters, Geli and Elfriede, accompanied their mother when she became Hitler's housekeeper in 1925; Geli Raubal was 17 at the time and would spend the next six years in close contact with her half-uncle. Her mother was given a position as housekeeper at the Berghofvilla near Berchtesgaden in 1928. Geli moved into Hitler's Munich apartment in 1929 when she enrolled in the Ludwig Maximilian University to study medicine. She did not complete her medical studies.

As he rose to power as leader of the Nazi Party, Hitler kept a tight rein over his half-niece and behaved in a domineering and possessive manner. When he discovered she was having a relationship with his chauffeur, Emil Maurice, he forced an end to the affair and dismissed Maurice from his service. After that he did not allow her to freely associate with friends, and attempted to have himself or someone he trusted near her at all times, accompanying her on shopping trips, to the movies, and to the opera.

Hitler's half-niece, Geli Raubal took her own life in 1931. Rumours immediately began in the media about a possible sexual relationship, and even murder. Historian Ian Kershaw contends that stories circulated at the time as to alleged "sexual deviant practices ought to be viewed as ... anti-Hitler propaganda".

After having little contact with her brother Adolf, Paula was delighted to meet him again in Vienna during the early 1930s.[58]By her own account, after losing a job with a Viennese insurance company in 1930 when her employers found out who she was, Paula received financial support from her brother (which continued until his suicide in late April 1945). She lived under the assumed family name Wolf at Hitler's request (this was a childhood nickname of his which he had also used during the 1920s for security purposes) and worked sporadically. She later claimed to have seen her brother about once a year during the 1930s and early 1940s.[citation needed]

When the NSDAP won 107 seats in the Reich parliament in 1930, the Times Union in Albany, NY, published a statement of Alois Jr.[59]

Angela strongly disapproved of Adolf's relationship with Eva Braun; she eventually left Berchtesgaden as a result and moved to Dresden. Hitler broke off relations with Angela and did not attend her second wedding. On 20 January 1936 she married German architect Professor Martin Hammitzsch, the Director of the State School of Building Construction in Dresden.[citation needed]

Second World War[edit]

As Hitler led Germany into the Second World War, he became distant from his family. Despite having previously become estranged after disapproval of Adolf's relationship with Eva Braun, Angela and Adolf eventually re-established contact during the war. Angela was his intermediary to the rest of the family, because Adolf did not want contact. In 1941, she sold her memoirs of her years with Hitler to the Eher Verlag, which brought her 20,000 Reichsmark. Meanwhile, Alois Jr. continued to manage his restaurant throughout the duration of the war. He was arrested by the British, but released when it became clear he had played no role in his brother's regime.

Adolf's other nephew, Leo Rudolf Raubal, was conscripted into the Luftwaffe. He was injured in January 1943 during theBattle of Stalingrad,[60] and Friedrich Paulus asked Hitler for a plane to evacuate Raubal to Germany.[61] Hitler refused and Raubal was captured by the Soviets on 31 January 1943. Hitler gave orders to check out the possibility of a prisoner exchange with the Soviets for Stalin's son Yakov Dzhugashvili, who was in German captivity since 16 July 1941.[62] Stalin refused to exchange him either for Raubal or for Friedrich Paulus,[63] and said "war is war."[64]

In the spring of 1945, after the destruction of Dresden in the massive bomb attack of 13/14 February, Adolf moved Angela toBerchtesgaden to avoid her being captured by the Soviets. Also, he let her and his younger sister Paula have over 100,000Reichsmark. Paula barely saw her brother during the war. There is some evidence Paula shared her brother's strongGerman nationalist beliefs, but she was not politically active and never joined the Nazi Party.[65] During the closing days of the war, at the age of 49, she was driven to Berchtesgaden, Germany, apparently on the orders of Martin Bormann.

Post-Second World War[edit]

In Hitler's last will and testament, he guaranteed Angela a pension of 1,000 Reichsmark monthly. It is uncertain if she ever received a penny of this amount. Nevertheless, she spoke very highly of him even after the war, and claimed that neither her brother nor she herself had known anything about the Holocaust. She declared that if Hitler had known what was going on in the concentration camps, he would have stopped them.

Adolf's sister Paula was arrested by US intelligence officers in May 1945 and debriefed later that year.[67] A transcript shows one of the agents remarking she bore a physical resemblance to her sibling. She told them the Russians had confiscated her house in Austria, the Americans had expropriated her Vienna apartment and that she was taking English lessons. She characterized her childhood relationship with her brother as one of both constant bickering and strong affection. Paula said she could not bring herself to believe her brother had been responsible for the Holocaust. She also told them she had met Eva Braun only once. Paula was released from American custody and returned to Vienna, where she lived on her savings for a time, then worked in an arts and crafts shop.

Other relatives of Hitler were approached by the Soviets. In May 1945, five of Hitler's relatives were arrested, his first cousins, Maria, Johann and Eduard Schmidt, along with Maria's husband Ignaz Koppensteiner, their son Adolf, and Johann Schmidt, Jr., son of Maria and Eduard's deceased brother Johann. Koppensteiner was arrested by the Soviets on the basis that he "approved of [Hitler's] criminal plans against the USSR." He died in a Moscow prison in 1949. Both Eduard and Maria died in Soviet custody in 1951 and 1953, respectively. Johann Jr. was released in 1955. These relatives were posthumously pardoned by Russia in 1997.[68][69][70]

In 1952, Paula Hitler moved to Berchtesgaden, reportedly living "in seclusion" in a two-room flat as Paula Wolff. During this time, she was looked after by former members of the SS and survivors of her brother's inner circle.[67] In February 1959, she agreed to be interviewed by Peter Morley, a documentary producer for British television station Associated-Rediffusion. The resulting conversation was the only filmed interview she ever gave and was broadcast as part of a programme calledTyranny: The Years of Adolf Hitler. She talked mostly about Hitler's childhood. Angela died of a stroke on 30 October 1949. Her brother, Alois Jr., died on 20 May 1956 in Hamburg. At that time, his name was Alois Hiller.[71] Paula, Adolf's last surviving sibling, died on 1 June 1960, at the age of 64.[72]

Alleged children[edit]

It is alleged that Hitler had a son, Jean-Marie Loret, with a Frenchwoman named Charlotte Lobjoie. Jean-Marie Loret was born in March 1918 and died in 1985, aged 67.[73] Loret married several times, and had up to nine children. His family's lawyer has suggested that, if their descent from Hitler could be proven, they may be able to claim royalties for Hitler's book,Mein Kampf.[74] However, several historians such as Anton Joachimsthaler,[75] and Sir Ian Kershaw,[76] say that Hitler's paternity is unlikely or impossible to prove.

Just two of Hitler's siblings and half-siblings, Angela and Alois, married.

Angela married Leo Raubal Sr. (1879-1910). They had three children: Leo Rudolf Raubal Jr had one son, Peter Raubal, in 1931; Geli Raubal committed suicide without having ever had a child in 1931; and Elfriede Raubal who married Dr. Ernst Hochegger in 1937 and had a son, Heiner Hochegger, in 1945. Both of Angela's grandsons, Peter and Heiner, have had no children.

Alois's son Heinz from his second marriage died in a Soviet military prison in 1942 without children. Alois's son from his first marriage, William Patrick, married Phyllis Jean-Jacques in 1947 in the US, where they had four children. Alexander Adolf Stuart-Houston (1949), Louis Stuart-Houston (1951), Howard Ronald Stuart-Houston (1957), and Brian William Stuart-Houston (1965) have all had no children;.[77] Only Howard, who died in a car crash in 1989, was ever married.

According to David Gardner, author of the Last of the Hitlers: "They didn’t sign a pact, but what they did is, they talked amongst themselves, talked about the burden they’ve had in the background of their lives, and decided that none of them would marry, none of them would have children. And that’s...a pact they’ve kept to this day."[78] Though none of Stuart-Houston's sons had children, his son Alexander, now a social worker, said that contrary to this speculation, there was no pact to intentionally end the Hitler bloodline.